Theory🔗

Sometimes, while working on complex code bases that are executed in UNIX systems, we need to have different processes communicate with each other. This approach is broadly called inter-process communication (IPC), and there are many similar but different ways in which this can be achieved. The most basic one is using standard input/output (stdio) to set up such communication. In this article we shall take a deep-dive into this approach hoping to demystify it.

For it to be at least somewhat practical, we provide some snippets and tips at the end of this article. An additional practical benefit of this article is that we use Zig code snippets in this article to illustrate the concepts. If you always were interested in what this language looks like and how to work with it, this article is for you.

Files!🔗

If there was a UNIX musical ever made, in the tradition of punchy single-word musical names, it would be called "Files!". There is an old adage that everything in UNIX is a file. It holds true for stdio, even though the three stdio files are device files, not regular files! We shall touch on this down the line.

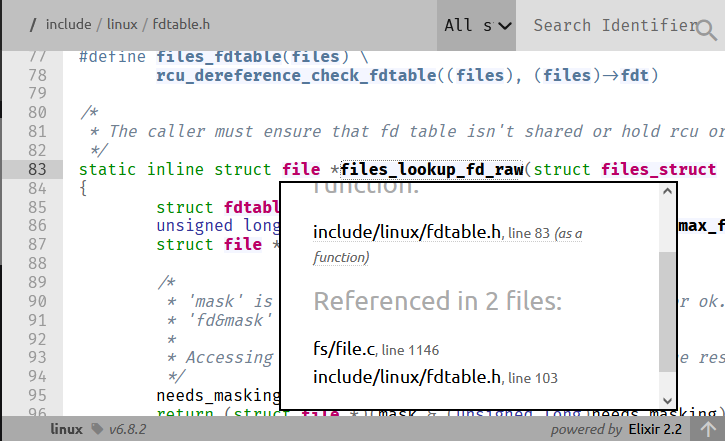

In Linux, every process has a data structure called files_struct, which holds fdtable, which provides a low-level interface to all the file descriptors currently associated with said process.

/*

* The caller must ensure that fd table isn't shared or hold rcu or file lock

*/

static inline struct file *files_lookup_fd_raw(

struct files_struct *files,

unsigned int fd

) {

struct fdtable *fdt =

rcu_dereference_raw(files->fdt);

unsigned long mask =

array_index_mask_nospec(fd, fdt->max_fds);

struct file *needs_masking;

/*

* 'mask' is zero for an out-of-bounds fd,

* all ones for ok.

* 'fd&mask' is 'fd' for ok,

* or 0 for out of bounds.

*

* Accessing fdt->fd[0] is ok,

* but needs masking of the result.

*/

needs_masking =

rcu_dereference_raw(fdt->fd[fd&mask]);

return

(struct file *)

(mask &

(unsigned long)needs_masking

);

}

Low-level file descriptor lookup. include/linux/fdtable.h, Kernel v6.8.2.

Note that it stores the descriptors of all the files, not just the open ones.

Kernel routines can verify if a file is open by calling fd_is_open(unsigned int fd, const struct fdtable *fdt) on a given file descriptor table.

Hint! If you want to easily look up and cross-reference identifiers in Linux kernel, you can use Bootlin cross-referencer, hosted over at https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v6.8.2/source.

Processes are forked with sys_clone(), which is a generic process forking routine.

It is a macro-wrapper around kernel_clone(), which eventually copies all the file descriptors from the parent proces in the most intricate copy_process().

It happens after tracer setup, and only after the descriptors are copied, the information about the newly forked process is relayed to the scheduler.

The function that performs the copying of the files_struct is copy_files() and it will do what it says on the tin unless clone argument no_files is set (see struct kernel_clone_args defined in sched/task.h).

To illustrate the semantics of copy_files(), let's have a look at the following Zig code:

const std = @import("std");

pub fn main() !void {

const message = "Hello, world!\n";

// Write and create

const flags = std.os.O.WRONLY | std.os.O.CREAT;

const fd = try std.os.open("./output.txt", flags, 0o644);

const pid = try std.os.fork();

if (pid == 0) {

std.os.nanosleep(0, 100_000_000);

std.debug.print("[CHILD] Attempting to write to fd.\n", .{});

try fds("CHILD");

// This write will happen because file descriptors are duplicated independently

// even though we shall close the file descriptor corresponding to `output.txt`

// shall be closed by the parent process immediately after forking.

//

// A system call similar to `dup2()` is used.

//

// `dup2()` makes susre that the integer associated with the file descriptor

// is preserved after dupplication.

// For stdio, it ensures that STDIN shall be 0, STDOUT -- 1, etc.

const result = try std.os.write(fd, message);

if (result != message.len) {

std.debug.print("[CHILD] Failed to write to fd.\n", .{});

std.os.exit(1);

} else {

std.debug.print("[CHILD] We do what we must because we can.\n", .{});

std.os.exit(0);

}

} else {

std.debug.print("[PARENT] Closing fd immediately.\n", .{});

std.os.close(fd);

try fds("PARENT");

// Wait for child process to exit

const wpr = std.os.waitpid(pid, 0x00000000);

// Check if the child exited with an error due to closed STDIN

if (std.os.W.IFEXITED(wpr.status) and std.os.W.EXITSTATUS(wpr.status) == 0) {

std.debug.print("[PARENT] This was a triumph.\n", .{});

}

}

}

// Dummy function to print active file descriptors, ignore for the time being

pub fn fds(_: [*:0]const u8) !void {}

You see that we fork a process here and let the parent process close output.txt by waiting in the child for 100 milliseconds.

As we described above, the files are copied to the child at fork time, so it doesn't matter that the file is closed by parent.

The child has the copied file "alive", so fd resolves to an open file in files_struct.

To illustrate this point further, we would like to query files_struct, but to my knowledge we can't do it with libc facilities or otherwise.

We can, however, get the information about the file descriptors tracked by kernel by querying /proc/self/fd.

Let's implement the dummy fds function from the previous example.

pub fn fds(whose: [*:0]const u8) !void {

var dir = try std.fs.openIterableDirAbsolute("/proc/self/fd", .{});

defer dir.close();

var it = dir.iterate();

while (try it.next()) |entry| {

if (entry.kind == .sym_link) {

var resolved_path:

[std.fs.MAX_PATH_BYTES]u8 = undefined;

const sl_resolved_path =

try std.os.readlinkat(

dir.dir.fd,

entry.name,

&resolved_path

);

std.debug.print("[{s}] FD {s}: {s}\n", .{ whose, entry.name, sl_resolved_path });

}

}

}

As we run this in a clean terminal, we get output that confirms that output.txt was, indeed, closed from the parent process.

λ zig build run-01B-fd-forward && cat output.txt

[PARENT] Closing fd immediately.

[PARENT] FD 0: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT] FD 1: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT] FD 3: /proc/455/fd

[CHILD] Attempting to write to fd.

[CHILD] FD 0: /dev/pts/19

[CHILD] FD 1: /dev/pts/19

[CHILD] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[CHILD] FD 3: /home/sweater/flake-mag/001/01/output.txt

[CHILD] FD 4: /proc/456/fd

[CHILD] We do what we must because we can.

[PARENT] This was a triumph.

Hello, world!

In the snippet above we have demonstrated how to make use of the standard low level functions to open and close files. Now let's demonstrate that the same functions can be used to work with stdio files. As well as that, let's demonstrate that indeed if a file, even one of stdio files, is closed, it won't be copied by Linux kernel to the forked process.

pub fn main() !void {

try fds("PARENT_BEFORE");

// Close standard file descriptors

std.os.close(0);

try fds("PARENT_NO_STDIN");

std.os.close(1);

try fds("PARENT_NO_STDOUT");

// std.os.close(2); // Leave STDERR open for debugging

const pid = try std.os.fork();

if (pid == 0) {

try fds("CHILD");

const stdin_fd = 0; // STDIN file descriptor

var buf = [_:1]u8{0};

std.debug.print("[CHILD] Attempting to read from STDIN...\n", .{});

_ = std.os.read(stdin_fd, &buf) catch std.os.exit(1);

std.debug.print("[CHILD] Read from STDIN: {s}\n", .{buf});

std.os.exit(0);

} else {

try fds("PARENT_AFTER");

const wpr = std.os.waitpid(pid, 0x00000000); // Wait for child process to exit

// Check if the child exited with an error due to closed STDIN

if (std.os.W.IFEXITED(wpr.status) and std.os.W.EXITSTATUS(wpr.status) == 1) {

std.debug.print("[PARENT] Child process confirmed that STDIN is closed.\n", .{});

} else {

std.debug.print("[PARENT] Child process did not behave as expected.\n", .{});

}

}

}

This code uses fds function just like in the previous example.

When you inspect the output of this command, note that file descriptor 0 is allocated to /proc/26202/fd due to us opening a file descriptor in fds function.

The first unused file descriptor shall be used.

In this case, since we closed STDIN, it is 0.

If you were wondering if closing stdio files is a good idea, I hope that this curious side effect shall be enough to convince you that it isn't a good idea indeed.

λ zig build run-01A-closed-stdio

[PARENT_BEFORE] FD 0: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_BEFORE] FD 1: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_BEFORE] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_BEFORE] FD 3: /proc/26202/fd

[PARENT_NO_STDIN] FD 0: /proc/26202/fd

[PARENT_NO_STDIN] FD 1: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_NO_STDIN] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_NO_STDOUT] FD 0: /proc/26202/fd

[PARENT_NO_STDOUT] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[PARENT_AFTER] FD 0: /proc/26202/fd

[PARENT_AFTER] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[CHILD] FD 0: /proc/26203/fd

[CHILD] FD 2: /dev/pts/19

[CHILD] Attempting to read from STDIN...

[PARENT] Child process confirmed that STDIN is closed.

You can see that file descriptors 0, 1, and 2 are set both for parent and the child.

Of course, most, if not all, the materials online on stdio will tell you that these are three special files that get passed from parent to child.

But if we look at the process initiation code or, in fact, aforementioned copy_files function, we will see that there is no special treatment of any files in files_struct whatsoever!

static int copy_files(

unsigned long clone_flags,

struct task_struct *tsk,

int no_files

) {

struct files_struct *oldf, *newf;

int error = 0;

/*

* A background process may not have any files ...

*/

oldf = current->files;

if (!oldf)

goto out;

if (no_files) {

tsk->files = NULL;

goto out;

}

if (clone_flags & CLONE_FILES) {

atomic_inc(&oldf->count);

goto out;

}

newf = dup_fd(oldf, NR_OPEN_MAX, &error);

if (!newf)

goto out;

tsk->files = newf;

error = 0;

out:

return error;

}

Routine that copies files in the kernel doesn't have any special treatment for stdio. kernel/fork.c, Kernel 6.8.2.

As a matter of fact, we can scour the entirety of kernel codebase responsible for files and processes for stdio-related stuff, we will find naught.

In the following section, we discuss how stdio files actually come into existence.

From Whence You Came🔗

The earliest place where we find our elusive stdio files is console_on_rootfs() function.

As the kernel gets unpacked (head.S -> start_kernel -> ...), a file /dev/console gets populated by initramfs.

Afterwards, this file gets multiplexed into three file descriptors and an early console driver will use it to organise its stdio.

/* Open /dev/console, for stdin/stdout/stderr, this should never fail */

void __init console_on_rootfs(void)

{

struct file *file = filp_open("/dev/console", O_RDWR, 0);

if (IS_ERR(file)) {

pr_err("Warning: unable to open an initial console.\n");

return;

}

init_dup(file);

init_dup(file);

init_dup(file);

fput(file);

}

Early console is the first place where stdio appears during Linux boot process. init/main.c, Kernel 6.8.2.

Note! While normally stdio is populated using

dup2()system call, early console setup does it differently. It uses a custom file descriptor duplication technique to prevent race conditions. Under the hood, it uses read-copy-update (RCU) synchronization mechanism which:

- Removes the pointer to the early file descriptor table, preventing new read attempts.

- Waits for its readers to complete critical sections of working with the data behind the original pointer.

- Frees (or otherwise rearranges) memory section after all the existing readers reported that their critical sections are completed.

A good example of RCU strategy from daily computer use would be the way Firefox browser forces restart after upgrade. It lets the user finish their work in the existing tabs, but shan't allow a new tab to be opened, prompting browser restart.

Streams of the Multitudes🔗

Looking at the code snippets, you may already understand how does it happen that standard input-outputs of various programs don't cross-pollute. Let's discuss it with more precision, however.

First of all, we should be clear that /dev/console file we have seen and, indeed, the /dev/pts/19 file we have seen, aren't regular files like a text file.

Note! The letters

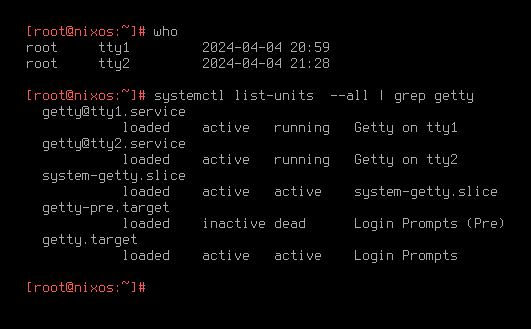

ptinptsstand for "pseudo-terminal", andsstands for an archaic word meaning "secondary". Pseudo-terminals shouldn't be confused with virtual terminals! A virtual terminal is an emulator of a hardware terminal in software. Linux without graphical server running such aswaylandorX11creates a bunch of consoles that are connected to their own virtual terminal via/dev/tty{0,1,...}devices. Pt-main and pt-secondary (named differently in Linux Kernel) are acquired viaopenpty()call fromlibc. Virtual terminals are created withgetty()call from the kernel.

Linux kernel defines many file kinds, confirming what we said in the introduction that "everything is a file" adage is less nuanced than the reality. Here are the kinds of files:

- Block device: your hard drives and other possible devices that stored data in fixed-size blocks. These normally provide random access.

- Character device: your keyboards, mice, serial ports. Devices that emit and consume data byte-by-byte. Random access is rare.

- Directory: a file that only can refer to other files. That's the most elegant way to conceptually define directories.

- Named pipe: unidirectional data flow and operates on a first-in-first-out basis. Unlike regular files, it doesn't store data persistently; it simply passes it from the writer to the reader. Anonymous pipes are created with

|, but you can make a named pipe withmkfifo. - Symlink: a file that contains exactly one reference to another file. Can be thought of as a "shortcut".

- File: a byte-aligned file holding some data. This kind of file is what people imagine when you say "a file". Hence the name.

- UNIX domain socket: a socket that behaves like a TCP/IP socket, except is using file system for data transfer.

Based on the descriptions of the file kinds above, you can guess what sort of files are stored in /dev/pts, but let's verify it:

const std = @import("std");

pub fn print_kinds(from: []const u8) !void {

var dir = try std.fs.openIterableDirAbsolute(from, .{});

defer dir.close();

var it = dir.iterate();

while (try it.next()) |entry| {

// Switch on entry.kind

switch (entry.kind) {

.block_device => std.debug.print("block device: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.character_device => std.debug.print("character device: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.directory => std.debug.print("directory: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.named_pipe => std.debug.print("named pipe: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.sym_link => std.debug.print("sym link: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.file => std.debug.print("file: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

.unknown => std.debug.print("unknown: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

else => std.debug.print("non-linux: {s}\n", .{entry.name}),

}

}

}

pub fn main() !void {

try print_kinds("/dev/pts");

}

A zig program that prints the kinds of the files in a given directory.

The output of this program is as follows:

character device: 0

character device: 2

character device: 1

character device: ptmx

An output of try print_kinds("/dev/pts").

Surprisingly, we have discovered ptmx character device.

We won't get into many details about its inner workings in this article, but we will explain what is the idea behind it.

Root-owned ptmx (pseudo-terminal multiplexer) is the key to how pseudo-terminal devices are created.

crw--w---- 1 sweater tty 136, 0 Apr 4 21:46 0

crw--w---- 1 sweater tty 136, 1 Apr 1 03:38 1

crw--w---- 1 sweater tty 136, 2 Apr 1 03:38 2

c--------- 1 root root 5, 2 Mar 31 06:32 ptmx

An output of ls -la /dev/pts.

For your terminal emulator to work, it needs a PTM device and a PTS device. Main pseudo-terminal device has no path attached to it and is used for coordination of the terminal state via I/O operations. It also is solely responsible for orchestration of session management.

Secondary pseudo-terminal device is a file linked directly to the terminal emulator's frontend. Writing into it causes input to be relayed to PTM and normally displayed on screen.

Some time ago, users of Linux kernel could just make PTM/PTS pairs ad hoc.

However, as the amount of objects flying around in /dev grew, a necessity appeared to centralised the task of giving out PTM/PTS pairs.

This is how ptmx was conceived.

System calls perform I/O on ptmx to have Linux Kernel create a PTM/PTS pair and return it for use of the process.

Because PTS is merely an I/O orchestration tool which doesn't actually store any data, the following properties hold true for it:

- You can't assume to be able to seek stdio, once you flush bytes into a stdio file, they generally can only be sequentially consumed by a reader.

- One does not simply attache to a pts device file or to a tty file in hopes to be able to read stdio contents. It is a device file the role of which is to perform side effects.

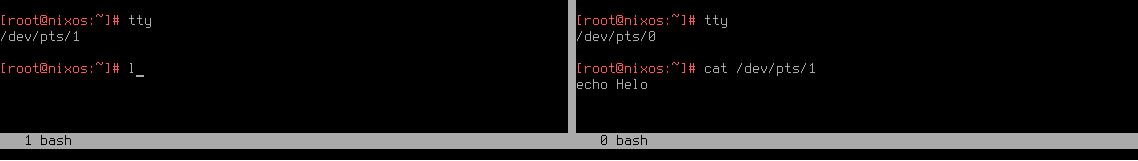

As a matter of fact, you can conduct the following experiment:

- Get PTS device number of your pseudo-terminal by running

tty. - Start reading from it from another terminal with

cat /dev/pts/$pts_id - Try typing

echo Hellointo the first pseudo-terminal.

What you will observe is that your keypresses are either consumed by cat or displayed in your terminal emulator because keypress got through to PTM, which resulted in characters being drawn on the screen via PTS, but not both at the same time.

I don't know if you find it to be a funny prank, but the behaviour of the active console is sure confusing.

As you can see in the code of your favourite terminal emulator, a pair of PTM and PTS is obtained via an openpty(&main, &secondary, ...).

Then, the PTS component of this pair shall be exactly the file which is going to be duplicated with dup2 and serve as the stdio file, serving both STDIN, STDOUT and STDERR.

int

ttynew(const char *line, char *cmd, const char *out, char **args)

{

int m, s;

if (out) {

term.mode |= MODE_PRINT;

iofd = (!strcmp(out, "-")) ?

1 : open(out, O_WRONLY | O_CREAT, 0666);

if (iofd < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error opening %s:%s\n",

out, strerror(errno));

}

}

if (line) {

if ((cmdfd = open(line, O_RDWR)) < 0)

die("open line '%s' failed: %s\n",

line, strerror(errno));

dup2(cmdfd, 0);

stty(args);

return cmdfd;

}

/* seems to work fine on linux, openbsd and freebsd */

if (openpty(&m, &s, NULL, NULL, NULL) < 0)

die("openpty failed: %s\n", strerror(errno));

switch (pid = fork()) {

case -1:

die("fork failed: %s\n", strerror(errno));

break;

case 0:

close(iofd);

close(m);

setsid(); /* create a new process group */

/**********/

dup2(s, 0);

dup2(s, 1);

dup2(s, 2);

/**********/

if (ioctl(s, TIOCSCTTY, NULL) < 0)

die("ioctl TIOCSCTTY failed: %s\n", strerror(errno));

if (s > 2)

close(s);

#ifdef __OpenBSD__

if (pledge("stdio getpw proc exec", NULL) == -1)

die("pledge\n");

#endif

execsh(cmd, args);

break;

default:

#ifdef __OpenBSD__

if (pledge("stdio rpath tty proc", NULL) == -1)

die("pledge\n");

#endif

close(s);

cmdfd = m;

signal(SIGCHLD, sigchld);

break;

}

return cmdfd;

}

Stdio in suckless terminal. st.c, st 0.9.

Doppelgang Paradox🔗

We already learned that it doesn't happen that three different device files are created for each entity in stdio.

But if it's the same file, how come they can be distinguished as data gets flushed into those?

Well, the short answer is that they can't be distinguished.

To a degree that even STDIN is opened with write permissions by default, which means you can write into it.

And indeed, when you write into STDIN, your terminal will behave in the same way as it would if you wrote into STDOUT or STDERR.

The three files, as far as your console is concerned, are truly doppelgangers.

const std = @import("std");

pub fn main() !void {

_ = try std.os.write(0, "Hello, world!\n");

}

This program will output "Hello, world!" in your terminal emulator.

However, since the meaning of STDIN being attached to PTS is to read user input, which is passed to PTS via PTM as a result of handling keypresses, this write shall be ignored and won't be read by the program shown in the next listing. The forked child here shall terminate only after a user presses a key, which shall be relayed to it via STDIN.

const std = @import("std");

pub fn main() !void {

const pid = try std.os.fork();

if (pid == 0) {

var buf = [_:255]u8{0};

_ = try std.os.read(0, &buf);

std.debug.print("Child read: {s}\n", .{buf});

} else {

std.os.nanosleep(0, 10_000);

_ = try std.os.write(0, "Hello, world!\n");

}

}

Note that this program will crash if you pipe something into it, because the pipe won't be opened for writing!

Thus, the only way to "un-dopplegang" stdio is to swap out some file descriptors.

The most common way to do so is by using pipes and redirections while invoking programs from a shell like bash.

Observe every stdio file being replaced in the following snippet.

λ ls -la /proc/self/fd <input.txt 2>output.err | tee output.txt

total 0

dr-x------ 2 sweater sweater 0 Apr 7 19:26 ./

dr-xr-xr-x 9 sweater sweater 0 Apr 7 19:26 ../

lr-x------ 1 sweater sweater 64 Apr 7 19:26 0 -> /tmp/input.txt

l-wx------ 1 sweater sweater 64 Apr 7 19:26 1 -> pipe:[3717804]

l-wx------ 1 sweater sweater 64 Apr 7 19:26 2 -> /tmp/output.err

lr-x------ 1 sweater sweater 64 Apr 7 19:26 3 -> /proc/19836/fd

Input is a file, the output is piped, while stderr is recorded into a regular file. bash 5.0.7.

Note!

teeis a very useful program for situations when you need to have an interactive session, traces of which you want to preserve for a later review or further automated manipulation. It displays whatever it gets into STDIN into STDOUT, but also records that data into file. Usetee -aif you want to append to file without overwriting.

Using stdio for IPC🔗

In the beginning of this article, we have seen how to write our own software that interacts with stdio.

As was shown in the last example, you could use pipes (|) and redirections (> and even <) to swap out your PTS with another file while spawning processes from a shell.

Let's now have a look at some examples of using stdio for IPC both when it comes to commonly used commands and from our code.

To pipe or not to pipe🔗

While learning Linux or other UNIX systems, one of the first sequence of commands we get acquainted with is "something something pipe grep".

Very often, however, we want to just grep contents of some file for some string.

Writing it as cat file.txt | grep string, however, is wasteful in the amount of file descriptors created (not that it particularly matters).

Instead, with what we learned about stdio from this article, we can just write grep string <file.txt.

This will directly substitute file descriptor 0 with a descriptor pointing at file.txt.

Input or argument🔗

An important consideration to choose whether or not use CLI arguments or stdio is the amount of data you want to shove into those. If those are simple strings, especially not something that needs escaping, using arguments is perfectly reasonable. While you can do the same with command-line arguments too, if you escape them, as seen in the next example, it's a bad design because it introduces unnecessary fragility.

Sun Apr 07 00:27:32:244240400 sweater@conflagrate /tmp

λ export x=$(cat <<EOF

Multiline

File

Name.txt

EOF

)

Sun Apr 07 00:27:38:754602700 sweater@conflagrate /tmp

λ echo "$x"

Multiline

File

Name.txt

Sun Apr 07 00:27:41:467729600 sweater@conflagrate /tmp

λ echo "Hello World" > "$x"

Sun Apr 07 00:27:52:976430800 sweater@conflagrate /tmp

λ cat Multiline$'\n'File$'\n'Name.txt

Hello World

Making a text file the name of which is a multiline string.

Note! The snippet above uses here-document feature of bash. It is a type of input redirection which creates a regular temporary file, writes to it whatever is between limit strings and redirects it into STDIN. After the redirection happens, the file gets deleted. For example, if you

<<intols -la /proc/self/fd, you will see an output akin to0 -> '/tmp/sh-thd.myfoxY (deleted)'.

Another reason to use STDIN to read "big" inputs is the flexibility it provides. A tool that calls your program won't need to format its output in any particular way. It may be relevant if, for instance, use JSON as to encode your IPC calls. In the next example, the program that emits solution can emit multiline JSON, single-line JSON or even weirdly-formatted JSON and the communication won't break down.

pub fn main() {

let arg_input = std::env::args().nth(1).expect("No input file provided");

let solution_str = std::io::stdin()

.lock()

.lines()

.next()

.expect("No solution provided")

.expect("Failed to read solution");

let solution =

Solution::new(

serde_json::from_str(&solution_str)

.expect("Failed to parse solution")

);

let input =

Input::from_json(

&PathBuf::from(arg_input)

).expect("Failed to read input file");

let forest = generate_forest(input.clone(), solution.clone());

let score = score_graph(&forest);

println!("{}", score);

}

Bending tools🔗

If you need to run your commands from some programmable tool such as make or npm, normally you can bend those tools to your will.

Since normally command runners execute commands inside a shell, you can leverage cat from inside the recipe to forward STDIN where you need it to be forwared.

As a bit of foreshadowing, to maintain clean STDOUT, in your make recipes, you should prefix the commands you call from the recipes with @.

In our challenge of capturing STDIN, we prefix cat.

check: target/release/checker

@cat | ./target/release/checker $(input)

In case of npm, you may do something like this.

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1",

"cat": "cat | index.js"

},

Bridge too Near🔗

While using STDIO for IPC, you really need to know how the underlying programs in your pipeline fork and whether or not they terminate when STDIN ends.

A classic example in practice is launching REPLs along with some data processing in a forked thread.

I personally got burned on that while working with BEAM languages such as Elixir, as in BEAM languages all things happen in a forked-off green thread.

So when you launch iex, Elixir REPL and expect to get some data from spawned processes, you will be disappointed.

To illustrate this in a more mainstream language, consider the following

import code

import threading

import time

results = {}

def background_task_do(t):

print(f"Starting background task: sleeping {t}s")

time.sleep(t)

results[t] = f"Finished after {t} seconds."

print(f"Task with t={t} done. results so far: {results}")

def background_task(t):

threading.Thread(

target=background_task_do,

args=(t,),

daemon=True

).start()

def main():

banner = """

Python 3 early exit demo. Available extra commands:

background_task(n) -> start a slow task that sleeps n seconds

results -> see which tasks have finished

Press Ctrl-D to exit the shell.

"""

local_env = {

"background_task": background_task,

"results": results,

}

code.interact(banner=banner, local=local_env)

print("\nExited the shell. Let's see if tasks completed.")

print("results =", results)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

This script spawns a Python REPL, which allows the user to use background_task(n) command to start a simulated slow task, which shall write something into results dict.

When you run it, you get dropped into a REPL and you can start a task:

❯ python3 early.py

Python 3 early exit demo. Available extra commands:

background_task(n) -> start a slow task that sleeps n seconds

results -> see which tasks have finished

Press Ctrl-D to exit the shell.

>>> background_task(5)

Starting background task: sleeping 5s

>>> background_task(3)

Starting background task: sleeping 3s

>>> background_task(1)

Starting background task: sleeping 1s

>>> Task with t=1 done. results so far: {1: 'Finished after 1 seconds.'}

Task with t=3 done. results so far: {1: 'Finished after 1 seconds.', 3: 'Finished after 3 seconds.'}

Task with t=5 done. results so far: {1: 'Finished after 1 seconds.', 3: 'Finished after 3 seconds.', 5: 'Finished after 5 seconds.'}

now exiting InteractiveConsole...

Exited the shell. Let's see if tasks completed.

results = {1: 'Finished after 1 seconds.', 3: 'Finished after 3 seconds.', 5: 'Finished after 5 seconds.'}

Now think what will happen if you now want to run this script as part of your pipeline, say, via echo "background_task(1)" | python3 early.py.

See the end of the article for the answer!

Han Shot First🔗

Another set of classic gotchas is the opposite to early termination. While using STDIO for IPC, you need to know that the programs will actually emit data into STDOUT and terminate when STDIN ends.

Here are some demonstrations using standard Linux utilities.

Lingering STDIN🔗

What if a program in your pipeline doesn't terminate when STDIN ends? Your pipeline will hang indefinitely, waiting for the program to finish.

Furthermore, if you aren't careful with the way you start your pipeline and the initial program actually doesn't write into STDOUT and hangs, you will end up with a deadlock.

tail -f - | cat

Mutual STDIN🔗

You also need to be careful not to assign STDIN of a downstream program to STDOUT. If you have code that somehow does what the following shell script does, you will end up with a deadlock.

mkfifo /tmp/pipeA

mkfifo /tmp/pipeB

cat /tmp/pipeA > /tmp/pipeB &

cat /tmp/pipeB > /tmp/pipeA

When make breaks🔗

Even though IPC with stdio is the simplest way to ensure data communicating between different processes, it's not without risks when it comes to using third party tools in the pipeline. We will finish this article with a recent bug that was plaguing our development team.

The system of interest for this example is a system which works with many binaries we have some control over, uses stdio for IPC. We build and run various these binaries with Makefiles using standard recipe API.

All the tests worked, including the big end-to-end test.

However, when we would run the whole system in development mode or on staging, everything worked except for the execution pipelines involving make.

The latter would fail with no-parse error while trying to process the data emitted into STDOUT by the child process.

The problem was that we were running staging and development environments with another make recipe

The purpose of this recipe was to make sure that the environment is set up and then pop an interactive system shell.

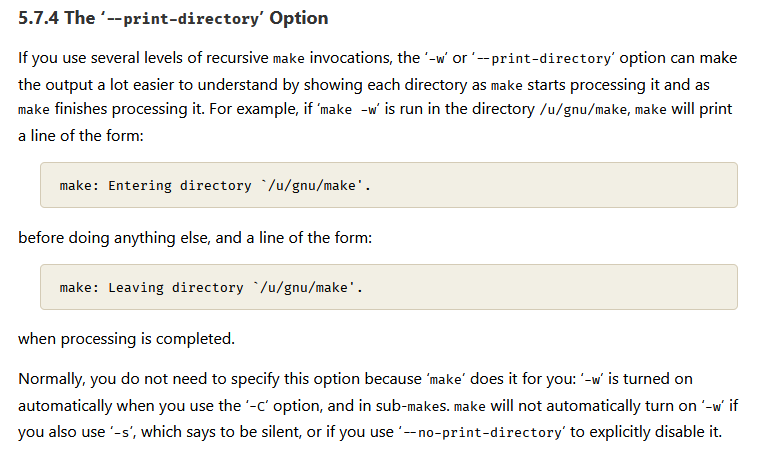

The reason for this weird bug is twofold:

make, against all the best practices, is printing diagnostic messages into STDOUT.- When

makeruns anothermakeunder the hood, it starts printing diagnostic messages, even though it doesn't do it when it's invoked at the top level.

These two factors ended up in pollution of STDOUT, which resulted in underlying programs not being able to parse the output. After we have pin-pointed the issue, the fix was simple.

λ git diff e019ee

diff --git a/bakery/src/singleplayer.rs b/bakery/src/singleplayer.rs

index f133d1d..653f395 100644

--- a/bakery/src/singleplayer.rs

+++ b/bakery/src/singleplayer.rs

@@ -169,6 +169,7 @@ pub fn simple_singleplayer(

// If everything is OK, run the checker

if let Ok(run_output) = &submission_output.run_output {

let mut checker_process = match Command::new("make")

+ .arg("--silent")

.arg("check")

.arg(format!("input={}", input.to_str().unwrap()))

.current_dir(checker) // Set the current directory to the checker directory

The final piece of advice we give you in this article is to always run make with --silent from your code!

Links to Code🔗

We hope you enjoyed this deep-dive into stdio, and hopefully now you feel like you know both its ins and outs. Some pun intended!

You can find code I wrote for this article here.

Answer to the Python Puzzle🔗

When you run the script with echo "background_task(1)" | python3 early.py, you will see that the task will not complete.

❯ echo 'background_task(1)' | python3 early.py

Python 3 early exit demo. Available extra commands:

background_task(n) -> start a slow task that sleeps n seconds

results -> see which tasks have finished

Press Ctrl-D to exit the shell.

>>> Starting background task: sleeping 1s

>>>

now exiting InteractiveConsole...

Exited the shell. Let's see if tasks completed.

results = {}